Hello dear blog readers! Here’s wishing you a very Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year!

Love,

Leopard

Photo by Richard Adams; published on guardian.co.uk

Yesterday, a young man entered an elementary school in Newtown, Connecticut, and opened fire on both staff and students, killing 20 children and 6 adults. It was later found that he had also killed his own mother, bringing his total victim count to 27.

Following the tragedy, news outlets and social media were ablaze with horror and misery, vigils were held for the victims and their families, and a nation mourned for the innocent lives so cruelly snatched away by a senseless act of brutality.

It is always heart-rending to hear about a school shooting. Yet, what I find even more upsetting is the fact that this is nothing new. We’ve seen it all before—in 2007 at Virginia Tech; in 2006 at Pennsylvania, in 2005 at Red Lake High School, Minnesota; in 1999 at Columbine High School—and so on. As President Obama tearfully said in a televised statement, America has “been through this too many times.” Each time it happens, we find ourselves shaking our heads in shock and bewilderment. Who is this guy? What is his personal history? What could have driven him to this? We obsess over the minutiae of the perpetrator’s psychology, treating it as an isolated, freak incident, while missing the larger pattern that is woven by each and every case. If we miss the pattern, then we cannot expect to find a solution. And without a solution, we are doomed to experience such tragedies over and over again.

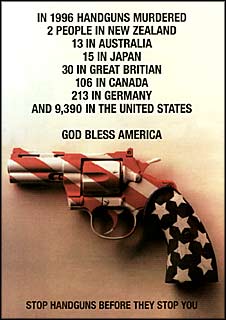

The Newtown shooting has reignited an ongoing debate about gun control in America, which is a promising start. Although America has always felt strongly about the right to bear arms (in a Gallup poll conducted last year, 55% felt that the gun laws should either remain the same or become even more lenient), public opinion is shifting towards gun control, with many taking to Twitter or Facebook to voice their support for tighter restrictions.

From changingworld.com

While I very much agree with the call for tighter gun control, and hope that Obama’s reference to “meaningful action” is more than just rhetoric, I feel that a fixation on the idea of guns as the main problem loses sight of the root of the issue. After all, 27 people died yesterday not because an out-of-control gun went on a rampage, but because a man picked up a gun, aimed, and pulled the trigger, 27 times. There are two issues that need attention here—the ease of obtaining and carrying a gun, but also the murderers themselves.

And when we do examine the perpetrators, there is a glaring pattern that is frequently overlooked; that is, the gendered dimension of the attacks. In response to yesterday’s shooting, The Telegraph did a short recap of the ten worst school shootings in the US. Out of this list, 100% of the perpetrators were male. About two months ago, Mother Jones ran a report on mass shootings in America. According to the article, there have been 62 incidents in the last 30 years, and 61 out of the 62 perpetrators were male. And according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, it is men who commit over 90% of violent crimes in America, and start 100% of wars.

The problem is, whenever people (usually feminists) point this out, they are met with cries of “misandry” and “demonization of men.” People (usually men) are quick to point out all the acts of heroism done by men, drawing attention to the brave policeman who saved countless civilians, to the self-sacrificing husband who protected his wife and children, frequently followed by a command to the female gender to be grateful to men for protecting them from, well, other men.

But if we want the level of violence in society to decrease, we cannot afford to ignore the gendered aspect of crime. We need to take a close look at male culture, and ask ourselves what lessons we teach young boys about what it means to be a man. We need to question the link between masculinity and power, between masculinity and dominance, and ask ourselves why little boys grow up needing to achieve both these qualities, which frequently translates into being either a hero or a villain. Most of all, we need to address the crisis in male emotional health, and ask ourselves why crying, expressing love, fear, or hurt, are emotional outlets that are denied to most men and boys. When the only emotion that a man can legitimately express is anger, how can we be surprised that many men turn to violence in response to emotional issues?

I do not buy biological reasons for male violence, especially since tests concerning the difference between male and female brains have largely been inconclusive. (For more on this, look up Delusions of Gender by neurologist Cordelia Fine.) Most men are not violent criminals, and to simply accept men’s near-monopoly on violence as a reflection on male nature is unfair. We as a society, with our rigid gender roles and our glorification of (male) aggression and power, continue to churn out violent men, and perpetuate the dynamic we were born into. But I firmly believe that we can also change it.

How many more young men have to be imprisoned before we acknowledge a problem with the values they’ve been brought up with? How many more children have to die, and how many more families have to grieve?

I’m ready for a safer world. And I know you are too.

Shame can arguably be said to be one of the worst emotions out there. Emotions like fear, grief and jealousy are strong contenders, and yet these feelings, strong as they are, don’t quite work in the same way that shame does. Dr Mary C. Lamia, a clinical psychologist, positions shame as unique in that it “lead[s] you to feel as if your whole self is flawed”, eating away at your sense of self-worth until you can no longer bear to face public scrutiny, or indeed, yourself.

Given the deep-reaching effects of shame, it is not surprising, then, that it makes a remarkably effective tool for maintaining the patriarchal order. Women are shamed for a whole host of reasons— for being fat, being ugly, being hairy, being an airhead, being sexually promiscuous, being sexually conservative—the list goes on. Men are shamed when they behave too much like women—when they show emotional sensitivity, when they dress like women, or enjoy traditionally feminine activities, or when they (horror of horrors) allow themselves to be subservient to a woman. The result is a preservation of the status quo, where men act in dominant, assertive, stoic ways, and women walk the fine line of adhering to decorative ideals, but careful not to take it so far that they are labelled ‘sluts’.

It all seems pretty straightforward when laid out this way, but the waters are muddied by the invisibility of these forces. Indeed, it would make things far less complicated if we could identify a group who had nefariously and deliberately devised these rules for the purposes outlined above. When a man laughs at another for being “pussywhipped”, he (usually) isn’t consciously thinking, “My friend doesn’t have power over his girlfriend. This is a threat to the position of men and women in society! What should I do? I know- I’ll mock him and make him feel humiliated. Everyone must know that this is an unacceptable position for a man to be in!” Likewise, when a woman talks about how fat another woman is, she isn’t trying to make a statement about the female obligation to always maintain our sexual attractiveness. No—they’re doing it because this is what they’ve always known, because they’ve never lived in a society that gave them an alternative lens through which to view men and women. And from a societal point of view, it doesn’t matter that their statement was merely a throwaway remark; the effects are the same as if we’d all pulled together and orchestrated it.

Next time we hear a friend engage in a bout of casual shaming, let’s make sure they have a little think about what they’re really saying. Let’s ask them why they feel that a woman’s worth is bound up with her sexual activity. And why they gave their male friend a high-five for sleeping with loads of women. Let’s ask them why Hillary Clinton’s appearance is relevant to her role in politics. And if they continue to think it appropriate to criticize politicians for completely random and irrelevant traits, ask them why they never thought to judge Obama’s competence based on his pottery skills. Ask why no newspaper has ever run a feature on how ugly David Cameron is. Finally, let’s ask them why they’re telling their sons that ‘being a gi-rl’ is the worst thing he can be. And what message that sends to their daughters.

Then let us reserve shame for activities that actually deserve it. Let violence, rape, and the exploitation of women be shameful. Let the horrors of war and mass murder be a source of shame, not glory. Let the next generation of children grow up knowing that shame will never touch them for abandoning gender roles, and give them a world defined by love and harmony, and not by domination and power.

Today, the 25th of November, is the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, ratified by the United Nations General Assembly in 1999.

Here are some sobering facts, taken from the United Nations site:

And lest we fall for the illusion that this is merely a problem in the developing world, here are a few stats that are a little closer to home:

In the UK, 1 in 4 women will be a victim of domestic violence in her lifetime, and an average of 2 women a week are killed by a current or former male partner.

In the US, approximately 1 in 5 female high school students reports being physically or sexually abused by a dating partner. 74% of Americans personally know someone who is or has been a victim of domestic violence.

Even Sweden, one of the most gender-equal countries in the world, has a problem with gender-based violence. An Amnesty report in 2005 highlighted how incidents of domestic violence against women were climbing, and the country was urged to take steps to curb it.

This is a global problem, and it has to end. Whether it’s ritualized violence like female genital mutilation and honour killings, organized violence like trafficking, or interpersonal acts of rape and assault, it all stems from the same notion – that women are not so much human as objects, to be bought and sold, to be brought under control, to serve, to please, and to be disciplined when we step out of line.

Collectively, we have spawned these norms, and collectively, we can change them. But we must do more than simply not be violent ourselves. We need to question and change the underlying attitudes towards women, question and change the link between violence and the assertion of masculinity. For the men reading this, you might be interested in The White Ribbon Campaign, which brings good men together to call attention to these issues, and to help the next generation of boys and men learn that violence is never the answer.

Too often, people don’t realize just how much power they have. Do something today to help raise awareness of the plight of women throughout the world, and make your voice heard. You may already be in the ranks of the brave women and men who work against violence everyday, but even if you aren’t, simple things matter– write on your Facebook wall, start a discussion with a friend, drop a letter to your MP, tweet about it– you’ll be surprised at the impact it can have.

This evening, I’m off to watch Stand Up to Sexism, a feminist comedy night jointly produced by the Everyday Sexism project and the No More Page 3 campaign. And so, I thought it appropriate for this week’s blog entry to discuss the oft-expressed opinion that “women aren’t funny.”

But is this true? The stats of women in improv and stand-up comedy are certainly dire. In 2010, Channel 4 in the UK ran a poll, asking its audience to vote for the 100 greatest stand-ups of all time. Only 6 on the list were women. Take a look at this Wikipedia list of stand-up comedians in the US–how many are women? Women rarely feature on the British comedy panel quiz show QI, and have only a meagre presence on my favourite improv show ‘Whose Line is it Anyway?’. To add insult to injury, the Whose Line women, with the exception of the brilliant Josie Lawrence, are not usually very funny.

What, exactly, is the problem here? Whenever feminists discuss the issue, we deny the blanket statement that women aren’t funny, and talk about our experiences of hilarious women in our lives. I’m going to chime in on this one– my female friends are just as funny, if not more so, than my male friends. But on the stage and on TV, there just don’t seem to be that many funny women around.

As with most phenomena in society to do with gender, people are far too eager to hop on the biological determinism bandwagon. Women, they confidently assert, just aren’t programmed to be funny. They’ll then proceed to work backwards from the status quo, coming up with some evolutionary reasoning for why the hunting male needed to be funnier than the berry-gathering female. But of course, these theories completely ignore the social context behind the dearth of female stand-up comedians. Looked at from this angle, a whole host of explanations spring to the fore.

Firstly, a successful female performer needs to fulfill two criteria. Not only does she need to be talented at what she does, she also needs to conform (far more than men do) to conventional standards of attractiveness to have a shot at making it on TV. Needless to say, this significantly reduces the pool of potential female comedians. Looking through the female guests on Whose Line, it does seem as though they are, to some extent, chosen for their attractiveness; a female version of Colin Mockery wouldn’t stand a chance.

Also, let’s not forget that ‘being funny’ is not an objective measure, and that what tickles us is largely shaped by our culture, gender, age and experiences. Even between the US and the UK, two countries that are (relatively) similar in culture, the difference in humour perception is very noticeable. Given that it is generally men who dominate public conversations and decide what is universally good (look at the judging panels for the Oscars, for instance, and comedy awards), it comes as little surprise that it is the comedians who share their sense of humour (read: fellow white men) who are celebrated.

Peter Nardi, a professor of sociology, wrote a paper on the relationship between gender and magic, and drew parallels between the masculine worlds of magic and comedy. He describes how stand-up has become “an entertainment field that…demands an aggressive, powerful role, involving one-upping people.” In his paper, he refers to several other studies which show how boys are socialised into “using speech to assert their dominance…to attract and maintain an audience.” Girls, on the other hand, are encouraged to form harmonious connections with others, and are discouraged from taking the floor, since this would establish a power imbalance between them and their audience through performance.

This may seem like a bit of a strange statement at first; after all, there are plenty of female performers around, and more girls than boys have experience in performance arts like dance, singing or acting. Yet, performing in Swan Lake is a far cry from performing as a stand-up comedian. It is nothing new for women to be the decorative vessels of male creativity– vehicles through which the genius of (often male) composers, choreographers and scriptwriters can be expressed. As a stand-up comedian, however, it is her own ideas and words that are heard, she herself who is manipulating the audience into laughter. This makes it difficult for female stand-ups to be accepted without initial resistance, and makes it unlikely that a young girl would view it as a feasible career choice for herself in the first place.

In my post about Seth Macfarlane’s Ted, I mentioned the excellent Richard Wiseman‘s study into the psychology of jokes. In line with the above theory of comedy and power, he writes, “People with high social status tend to tell more jokes than those lower down the pecking order. Traditionally, women have had a lower social status than men, and thus may have learnt to laugh at jokes, rather than tell them.” So, next time you hear someone going on about how women just aren’t funny, let them know that all they’re really observing is that women have always had a lower social status than men. Which we knew already, thanks.

Red poppies are everywhere. For the past few weeks, in tube stations and the streets, you could buy a little red paper poppy to pin on your jacket, to show your respect for the nation’s fallen soldiers in the lead up to Remembrance Day. Today, led by the Queen, politicians laid wreaths at the Cenotaph to honour the soldiers who had died in conflict, while the country observed two minutes of silence.

It’s all very solemn and respectful, but dig a little deeper, and the stench of their hypocrisy rises to the surface.

Here’s David Cameron, proudly wearing his poppy and ‘connecting’ with the Royal Marines. “We must remember forever, not just for today,” he says.

Photo by Steve Back. From http://www.telegraph.co.uk

The trouble is, does he remember? Does the nation remember? And what was the purpose of remembering? Was it not to remember the horrors and devastation of war? Was it not to celebrate the signing of the armistice? Was it not to learn from past mistakes, to ensure that present and future generations would never have to go through what our ancestors went through? If Britain’s leaders truly remember, why are they still so committed to militarism? Why have they spent £2 billion developing military drones over the past five years, with plans to spend a further £2 billion, while public services are being mercilessly cut? Why are British arms being sold to support Middle Eastern dictatorships? Why do soldiers continue to kill and be killed in needless wars in Afghanistan?

Or is it simply a sentimental, condescending pat on the head of the fallen and their relatives, a continuation of the glorification of war and violence as a way of resolving disputes? Through the rhetoric of honour and glory, they obscure the horrors and realities of war, and insist on creating new fallen heroes, even as they mourn the old ones.

Ben Griffin, an ex-SAS soldier, says,

“War is nothing like a John Wayne movie. There is nothing heroic about being blown up in a vehicle, there is nothing heroic about being shot in an ambush and there is nothing heroic about the deaths of countless civilians. Calling our soldiers heroes is an attempt to stifle criticism of the wars we are fighting in. It leads us to that most subtle piece of propaganda: You might not support the war but you must support our heroes, ergo you support the war. It is revealing that those who send our forces to war and those that spread war propaganda are the ones who choose to wear poppies weeks in advance of Armistice Day.”

It is worth bearing in mind that, as Laurie Penny points out, “not all of [the soldiers in the first and second world wars] bled willingly, for king and country; some of them simply bled because they had been seriously injured, because their leaders deemed it appropriate for them to die in pain and terror.” For government to talk reverently of “sacrifice” is to hijack the grief of veterans and their relatives to further their own jingoistic propaganda aims.

Despite a decrease in violence over the centuries, we are still in a society that is obsessed with the idea that ‘might is right’. Our national leaders pin poppies to their suits, bow their heads and mourn the fallen, while their hands drip with the blood of all the soldiers and civilians that they have slain, and will continue to slay.

Photo from http://www.britac.ac.uk

My formative years were spent in an all-girls secondary school with strong feminist values, and I was surrounded by teachers and classmates who took it as a given that women are strong, independent and capable. We were encouraged to strive for success and pursue our dreams, and so while many elements of the world struck me as unfair, sexism didn’t actually affect my student life all that much. Sadly, by the time I got to university, lad culture began to dominate the landscape, and the patriarchy started pushing itself in my face a little more. But although I hated the unequal gender relations I perceived, hated the bawdy jokes, the groping and grinding, and the predominance of male voices all over campus, I didn’t really see it as an obstacle to my success. After all, I was achieving good grades; assignments and exams were marked anonymously, so apart from bouts of feminist ranting to my family and friends, I still (very naïvely) saw it as purely a social issue, with not much impact on my path through life, or the possibilities that would be available to me.

Entering the working world was really what ignited my proper feminist awakening. I got a job in management at the trainee level, and suddenly, nothing was objective anymore. My success in the role was, in effect, measured by how much influence I could obtain, and I felt that nothing I did could be separated from my race and gender. Despite my good performance, senior managers would tease me, flirt with me, baby me and patronize me, in a way they never did with my fellow male trainees. Even the employees did this. I noticed the female senior managers getting the same treatment, and observing them, I realized that they had two options – play along, and gain a reputation for being nice (but be walked all over and lose control over the team), or be firm and effective (but be hated and called a bitch behind their backs). My increasing frustration with the situation galvanized me to discover more about the feminist movement, and I began raring to take action for change.

Of course, there is so much more to feminism than the issue of women in the workplace. Yet, addressing the poor representation of women in the workforce and in positions of power (politics, academia, the public sector, the media, business, etc) is critical to raising the profile of women in society, and making our voices heard. So last Wednesday, I was excited to attend “Where Are All the Women?”, a panel discussion hosted by the British Academy and The Culture Capital Exchange, designed to talk about pertinent issues holding women back in their careers today.

Chaired by the excellent Bidisha, the panel consisted of successful women like Rachel Millward (founder of Bird’s Eye View), Cressida Dick (Assistant Commissioner, London Met), and Professor Vicki Bruce, among others. A great deal of ground was covered over the course of the evening, from the shockingly low statistics of women’s representation in the film industry and FTSE 100 boards, to the question of maternity leave, to the devaluation of women’s work in the home, to the rigid gender roles society expects us to inhabit from a very young age. I’ll just pick out two points that I particularly liked-

Talking about the importance of any institution’s or industry’s image in attracting people to join them, Prof Vicki Bruce gave us an anecdote about her experience at the University of Edinburgh. Walking in, she noticed the walls covered with portraits of eminent people in the university’s history – and they were all white men. Of course, this was an accurate representation of their history rather than outright misogyny, but, as Vicki argued, the message that the university was sending out through this display, and the effect it might have on making people feel welcome (or not), was significant. She lobbied hard for change, and finally, the university responded by commissioning, and displaying, photographs of recent honorary graduates, representing a diverse spectrum of people. I sincerely hope that all institutions follow suit; you can’t change the inequalities in your history, but you should definitely do all you can to make sure those inequalities are not perpetuated.

Another issue I was happy to hear about is society’s warped ideas of leadership and command. We all know what qualities are valued in a leader – assertiveness, (over)confidence, the ability to stand one’s ground without giving in. And too often, we mistakenly take these signs as evidence of capability. On the contrary, traits like compassion, gentleness, thoughtfulness, cooperativeness and carefulness are dismissed, when they should be paramount. As Deborah Mattinson pointed out, if our current world and business leaders had these traits, maybe banks wouldn’t have failed so spectacularly and our economy would be the better for it. Maybe we would stop funding wars and devastation, and concentrate on social services instead.

Which is why I was surprised and a little peeved towards the end of the event, when some members of the panel criticized women for not being assertive enough, even gently mocking their own polite, turn-taking manner of discussion that evening. There was talk of how men were generally aggressive during debates, with women being unable to get a word in, and how we needed to step up, start putting ourselves forward and make our views known. On one hand, I agree that we have a problem with women’s lack of confidence and unwillingness to speak up, brought about through a lifetime of cultural conditioning. I agree that women too often discount their own opinions and are too quick to apologize for their views, and that we need to tackle this. But I am strongly against the idea that we should aspire to debate the way men do. The panelists may have made fun of their own politeness, but I actually found this to be one of the strengths of the discussion. As chair, Bidisha did an excellent job, and there was a high level of respect among the group, even when they disagreed. Most importantly, they listened to one another, considered one another’s ideas and had a genuine discussion, while at the same time opening it up to enable us to have our own thoughts on the matter. And by doing this, they avoided the most serious flaw in most (male-dominated) debates, which is viewing it as a competition. I have watched far, far too many discussions where the participants’ aim is not to discuss the issue or to learn from others to advance their own ideas, but to win at all costs. They interrupt, raise their voices and talk over each other; they are combatants, and changing their own mind or agreeing with something the other party has said is not to be thought of. Does either party learn anything except how to be more aggressive in future? How productive has it been? So I’m all for encouraging women to be more confident in expressing their ideas, but I also think that the male model of ‘discussion’, ‘argument’ and ‘debate’ desperately needs to change.

All in all, I’m glad that this discussion took place, and even happier that the organizers had to switch to a larger venue due to the overwhelming response. We urgently need to make such issues part of the wider national conversation, and until we achieve political, economic and social parity, we just won’t shut up.